|

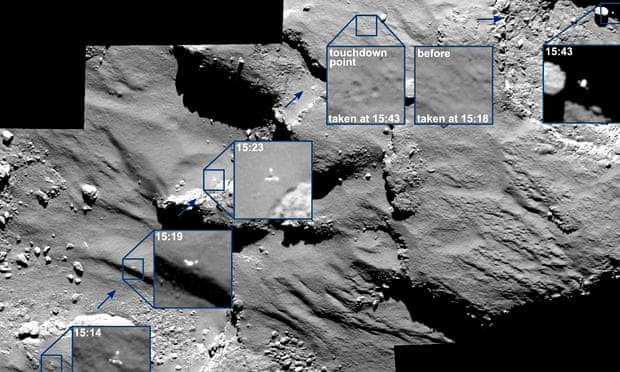

| Philae worked for more than 60 hours on the comet, which is more than 500m miles from Earth, before hibernating. Photograph: Handout/Reuters |

The Philae lander has found organic molecules – which are essential

for life – on the surface of the comet where it touched down last week.

The spacecraft managed to beam back evidence of the carbon and–hydrogen–containing chemicals shortly before it entered hibernation mode to conserve falling power supplies.

Although scientists are still to reveal what kind of molecules have been found on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, the discovery could provide new clues about how the early chemical ingredients that lead to life on Earth arrived on the planet.

Many scientists believe they may have been carried here on an asteroid or comet that collided with the Earth during its early history.

The DLR German Aerospace Centre, which built the Cosac instrument, confirmed it had found organic molecules.

It said in a statement: “Cosac was able to ‘sniff’ the atmosphere and detect the first organic molecules after landing. Analysis of the spectra and the identification of the molecules are continuing.”

The compounds were picked up by the instrument, which is designed to “sniff” the comet’s thin atmosphere, shortly before the lander was powered down.

It is believed that attempts to analyse soil drilled from the comet’s surface with Cosac were not successful.

Philae was able to work for more than 60 hours on the comet, which is more than 500m miles from Earth, before entering hibernation.

“We currently have no information on the quantity and weight of the soil sample,” said Fred Goesmann principal investigator on the Cosac instrument at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research.

Goesmann said his team were still trying to interpret the results, which will hopefully reveal whether the molecules contain other chemical elements deemed important for life.

Professor John Zarnecki, a space scientist at the Open University who was the deputy principal investigator on another of Philae’s instruments, described the discovery as “fascinating”.

“There has long been indirect evidence of organic molecules on comets as carbon, hydrogen and oxygen atoms have been found in comet dust,” he said.

“It has not been possible to see if these are forming complex compounds before and if this is what has been found then it is a tremendous discovery.”

Organic molecules, which are chemical compounds that contain carbon and hydrogen, form the basic building blocks of all living organisms on Earth.

They can take many forms from simple small molecules like methane gas to complex amino acids that make up proteins.

Philae landed on comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko after a 10-year journey through space aboard the Rosetta space probe. Philae’s initial attempt to touch down on the comet’s surface were unsuccessful when it failed to anchor itself properly, causing it to bounce back into space twice before finally coming to rest.

It meant the lander’s final resting place was about half a mile from the initial landing site and left Philae lying at an angle and its solar panels partially obscured.

In a desperate attempt to get as much science from the lander as possible before its meagre battery reserves ran out, scientists deployed a drill to bore down into the comet surface.

It is thought, however, that the drilling was unsuccessful and it failed to make contact with the comet.

But other findings from instruments on the lander, which were beamed back shortly before it powered down into a hibernation mode, suggest that the comet is largely composed of water ice that is covered in a thin layer of dust.

Preliminary results from the Mupus instrument, which deployed a hammer to the comet after Philae’s landing, suggest there is a layer of dust 10-20cm thick on the surface.

Beneath that is very hard water ice, which Mupus data suggests is possibly as hard as sandstone.

“It’s within a very broad spectrum of ice models. It was harder than expected at that location, but it’s still within bounds,” said Professor Mark McCaughrean, senior science adviser to Esa.

“You can’t rule out rock, but if you look at the global story, we know the overall density of the comet is 0.4g/cubic cm. There’s no way the thing’s made of rock.”

At Philae’s final landing spot, the Mupus probe recorded a temperature of –153°C before it was deployed and then once it was deployed the sensors cooled further by 10°C within half an hour.

“If we compare the data with laboratory measurements, we think that the probe encountered a hard surface with strength comparable to that of solid ice,” said Tilman Spohn, principal investigator for Mupus. Scientists hope that as comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko moves closer to the sun in the next few months, some light will start to reach Philae’s solar panels again, giving it enough power to come out of hibernation.

This could allow further analysis to take place on the surface.

“Until then we are going to have to make do with the data we have got,” said Zarnecki.

The spacecraft managed to beam back evidence of the carbon and–hydrogen–containing chemicals shortly before it entered hibernation mode to conserve falling power supplies.

Although scientists are still to reveal what kind of molecules have been found on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, the discovery could provide new clues about how the early chemical ingredients that lead to life on Earth arrived on the planet.

Many scientists believe they may have been carried here on an asteroid or comet that collided with the Earth during its early history.

The DLR German Aerospace Centre, which built the Cosac instrument, confirmed it had found organic molecules.

It said in a statement: “Cosac was able to ‘sniff’ the atmosphere and detect the first organic molecules after landing. Analysis of the spectra and the identification of the molecules are continuing.”

The compounds were picked up by the instrument, which is designed to “sniff” the comet’s thin atmosphere, shortly before the lander was powered down.

It is believed that attempts to analyse soil drilled from the comet’s surface with Cosac were not successful.

Philae was able to work for more than 60 hours on the comet, which is more than 500m miles from Earth, before entering hibernation.

“We currently have no information on the quantity and weight of the soil sample,” said Fred Goesmann principal investigator on the Cosac instrument at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research.

Goesmann said his team were still trying to interpret the results, which will hopefully reveal whether the molecules contain other chemical elements deemed important for life.

Professor John Zarnecki, a space scientist at the Open University who was the deputy principal investigator on another of Philae’s instruments, described the discovery as “fascinating”.

“There has long been indirect evidence of organic molecules on comets as carbon, hydrogen and oxygen atoms have been found in comet dust,” he said.

“It has not been possible to see if these are forming complex compounds before and if this is what has been found then it is a tremendous discovery.”

Organic molecules, which are chemical compounds that contain carbon and hydrogen, form the basic building blocks of all living organisms on Earth.

They can take many forms from simple small molecules like methane gas to complex amino acids that make up proteins.

Philae landed on comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko after a 10-year journey through space aboard the Rosetta space probe. Philae’s initial attempt to touch down on the comet’s surface were unsuccessful when it failed to anchor itself properly, causing it to bounce back into space twice before finally coming to rest.

It meant the lander’s final resting place was about half a mile from the initial landing site and left Philae lying at an angle and its solar panels partially obscured.

In a desperate attempt to get as much science from the lander as possible before its meagre battery reserves ran out, scientists deployed a drill to bore down into the comet surface.

It is thought, however, that the drilling was unsuccessful and it failed to make contact with the comet.

But other findings from instruments on the lander, which were beamed back shortly before it powered down into a hibernation mode, suggest that the comet is largely composed of water ice that is covered in a thin layer of dust.

Preliminary results from the Mupus instrument, which deployed a hammer to the comet after Philae’s landing, suggest there is a layer of dust 10-20cm thick on the surface.

Beneath that is very hard water ice, which Mupus data suggests is possibly as hard as sandstone.

“It’s within a very broad spectrum of ice models. It was harder than expected at that location, but it’s still within bounds,” said Professor Mark McCaughrean, senior science adviser to Esa.

“You can’t rule out rock, but if you look at the global story, we know the overall density of the comet is 0.4g/cubic cm. There’s no way the thing’s made of rock.”

At Philae’s final landing spot, the Mupus probe recorded a temperature of –153°C before it was deployed and then once it was deployed the sensors cooled further by 10°C within half an hour.

“If we compare the data with laboratory measurements, we think that the probe encountered a hard surface with strength comparable to that of solid ice,” said Tilman Spohn, principal investigator for Mupus. Scientists hope that as comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko moves closer to the sun in the next few months, some light will start to reach Philae’s solar panels again, giving it enough power to come out of hibernation.

This could allow further analysis to take place on the surface.

“Until then we are going to have to make do with the data we have got,” said Zarnecki.

0 comments:

Post a Comment