|

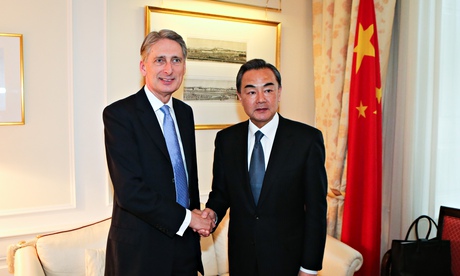

| Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi (right) meets with British foreign secretary Philip Hammond (left), 24 November 2014. Photograph: Zhang Fan/Xinhua Press/Corbis |

A visit by a cross-party group of parliamentarians to China, led by

Peter Mandelson, has been cancelled at the last minute after Beijing

refused to grant a visa to a Conservative MP in retaliation for a

Westminster debate on the recent pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong.

In a sign of Beijing’s sensitivity to international criticism of its response to the protests in Britain’s former colony, the Chinese embassy in London demanded that Richard Graham, MP for Gloucester, make a statement clarifying his thinking after he held the debate in Westminster Hall last month.

The MPs, who had been due to leave on Tuesday morning for the three-day visit to Shanghai, issued an ultimatum to the embassy: grant Graham, the chair of parliament’s all-party China group, a visa or the whole trip would be cancelled. The embassy failed to agree to their demands by 5pm on Monday, which meant the trip was cancelled.

Hugo Swire, the Foreign Office minister with responsibility for the Asia-Pacific region, was understood to have been involved in talks to try to save the trip and avoid a diplomatic row.

But members of the delegation, who included the former Labour cabinet minister and China expert Liam Byrne, shadow cabinet member Emma Reynolds, Conservative MPs Conor Burns and Alok Sharma, were understood to feel that the Chinese embassy was interfering in a wholly unacceptable way in the internal affairs of the UK. The trip was part of the UK-China Leadership Forum. Their attitude was described as regretful rather than angry.

A Foreign Office spokesman said: “The UK-China Leadership Forum has an important role in UK/China relations. We have raised this with the Chinese government and sought an explanation of their decision to deny a visa.”

Sources made clear that the Great British China Centre, which organised the trip, is independent of the government. The centre makes its own decisions about travel arrangements.

Graham, a former diplomat who served at the British embassy in Beijing and as the British consul in the former Portuguese colony of Macao in the late 1980s, used the debate in Westminster Hall on 22 October to voice support for some of the protesters’ demands. The protests were sparked by the decision of Beijing to impose restrictions on the election of Hong Kong’s next chief executive.

In a highly nuanced speech, designed to show his deep understanding of Chinese sensitivities while voicing support for the pro-democracy activists, Graham told MPs that Britain had a duty to uphold the principles of the 1984 joint declaration by Britain and China, which led to the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997. In the declaration China agreed to maintain “freedom under the law, an independent judiciary, a free press, free speech and the freedom to demonstrate”.

He added: “If we allow any of those freedoms to be curtailed and if we say nothing about any dilution of Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy, whether deliberate or inadvertent, we risk colluding in Hong Kong’s gradual – not immediate – decline, helping others in Asia who would swiftly take any opportunity at Hong Kong’s expense, and we would not be fulfilling the commitments that John Major, Robin Cook and, most recently, our prime minister have re-emphasised in the clearest terms.”

Graham, who was living in Hong Kong at the time of the 1984 declaration and the 1997 handover, tried to reassure Beijing on one of its main concerns: that outside powers were orchestrating the protests. He said: “It is my belief that most of those in Hong Kong who feel most strongly about the issues around the election of the next chief executive represent a new generation of Hong Kongers.

They were mostly born after the joint declaration. They are not, as has sometimes been claimed, ancient colonial sentimentalists or those left by dark foreign forces to create disturbance after the colonialists had gone, but a new generation with a different take on life from their predecessors. They are more sure of their Hong Kong identity, less sure of their future prospects and less trustful of government or leaders in whose appointment they still feel they do not have enough say.”

Graham concluded his speech by addressing two of Beijing’s long-held concerns: the need for stability and an assurance that Britain was not seeking to extend its influence back into its former colony.

He said: “Stability for nations is not, in our eyes, about maintaining the status quo regardless, but about reaching out for greater involvement with the people – in this case, of Hong Kong – allowing them a greater say in choosing their leaders and, above all, trusting in the people.

“We have no interest, no advantage or no conceivable selfish purpose in any form of car crash with Hong Kong’s sovereign master, China. Rather, it is in all our interests, but particularly those of Britain and China in fulfilling the joint declaration, that Hong Kong continues to thrive and prosper, in a different world from that of 1984 or even 1997.”

In a sign of Beijing’s sensitivity to international criticism of its response to the protests in Britain’s former colony, the Chinese embassy in London demanded that Richard Graham, MP for Gloucester, make a statement clarifying his thinking after he held the debate in Westminster Hall last month.

The MPs, who had been due to leave on Tuesday morning for the three-day visit to Shanghai, issued an ultimatum to the embassy: grant Graham, the chair of parliament’s all-party China group, a visa or the whole trip would be cancelled. The embassy failed to agree to their demands by 5pm on Monday, which meant the trip was cancelled.

Hugo Swire, the Foreign Office minister with responsibility for the Asia-Pacific region, was understood to have been involved in talks to try to save the trip and avoid a diplomatic row.

But members of the delegation, who included the former Labour cabinet minister and China expert Liam Byrne, shadow cabinet member Emma Reynolds, Conservative MPs Conor Burns and Alok Sharma, were understood to feel that the Chinese embassy was interfering in a wholly unacceptable way in the internal affairs of the UK. The trip was part of the UK-China Leadership Forum. Their attitude was described as regretful rather than angry.

A Foreign Office spokesman said: “The UK-China Leadership Forum has an important role in UK/China relations. We have raised this with the Chinese government and sought an explanation of their decision to deny a visa.”

Sources made clear that the Great British China Centre, which organised the trip, is independent of the government. The centre makes its own decisions about travel arrangements.

Graham, a former diplomat who served at the British embassy in Beijing and as the British consul in the former Portuguese colony of Macao in the late 1980s, used the debate in Westminster Hall on 22 October to voice support for some of the protesters’ demands. The protests were sparked by the decision of Beijing to impose restrictions on the election of Hong Kong’s next chief executive.

In a highly nuanced speech, designed to show his deep understanding of Chinese sensitivities while voicing support for the pro-democracy activists, Graham told MPs that Britain had a duty to uphold the principles of the 1984 joint declaration by Britain and China, which led to the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997. In the declaration China agreed to maintain “freedom under the law, an independent judiciary, a free press, free speech and the freedom to demonstrate”.

He added: “If we allow any of those freedoms to be curtailed and if we say nothing about any dilution of Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy, whether deliberate or inadvertent, we risk colluding in Hong Kong’s gradual – not immediate – decline, helping others in Asia who would swiftly take any opportunity at Hong Kong’s expense, and we would not be fulfilling the commitments that John Major, Robin Cook and, most recently, our prime minister have re-emphasised in the clearest terms.”

Graham, who was living in Hong Kong at the time of the 1984 declaration and the 1997 handover, tried to reassure Beijing on one of its main concerns: that outside powers were orchestrating the protests. He said: “It is my belief that most of those in Hong Kong who feel most strongly about the issues around the election of the next chief executive represent a new generation of Hong Kongers.

They were mostly born after the joint declaration. They are not, as has sometimes been claimed, ancient colonial sentimentalists or those left by dark foreign forces to create disturbance after the colonialists had gone, but a new generation with a different take on life from their predecessors. They are more sure of their Hong Kong identity, less sure of their future prospects and less trustful of government or leaders in whose appointment they still feel they do not have enough say.”

Graham concluded his speech by addressing two of Beijing’s long-held concerns: the need for stability and an assurance that Britain was not seeking to extend its influence back into its former colony.

He said: “Stability for nations is not, in our eyes, about maintaining the status quo regardless, but about reaching out for greater involvement with the people – in this case, of Hong Kong – allowing them a greater say in choosing their leaders and, above all, trusting in the people.

“We have no interest, no advantage or no conceivable selfish purpose in any form of car crash with Hong Kong’s sovereign master, China. Rather, it is in all our interests, but particularly those of Britain and China in fulfilling the joint declaration, that Hong Kong continues to thrive and prosper, in a different world from that of 1984 or even 1997.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment